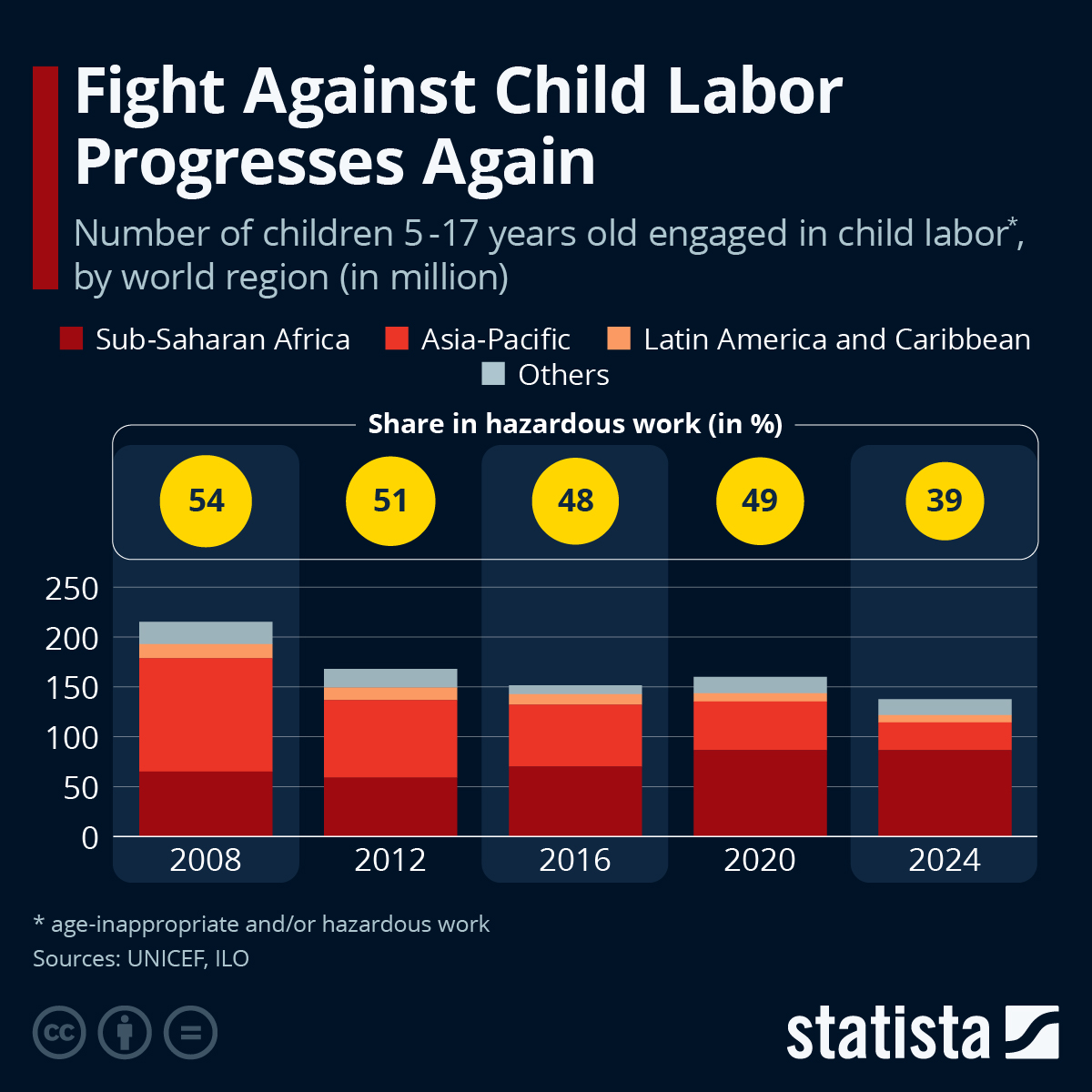

A report released yesterday by UNICEF and the International Labor Organization shows that even before the coronavirus pandemic came into full swing, progress in combating child labor around the world had stalled. At the beginning of 2020, there were once again 160 million children between the ages of 5 and 17 engaged in age-inappropriate and/or hazardous work. The new number marks an increase from around 152 million in 2016.

While child labor in Asia and Latin America has decreased, it has been rising again in Sub-Saharan Africa – in absolute and relative terms. While in 2016, 22.4 percent of children between the ages of 5 and 17 were in child labor in the region, that number had risen to almost 24 percent in early 2020. The global share of 9.6 percent of children engaged in child labor stayed the same between 2016 and 2020, showing that while the increase in child labor was in line with world population growth, the burden has shifted between regions.

The report also reveals that one of the most common images of child labor in the developing world – children working for a wage on factory floors – is actually the least common scenario. Child labor in industry stood at around 10 percent globally, being trumped by work in the service sector (around 20 percent) as well as the most common field for child labor, agriculture (70 percent). Earning a wage is also most uncommon for children, as 72 percent of child laborers work with their families.

Both numbers rise above 80 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa. The shift towards Africa therefore means that more young children below the age of eleven have become engaged in child labor, since agricultural and family work typically involve younger child workers. Yet, the region’s particular profile is more likely to keep child workers in school.

Child labor in Latin America and Asia typically involved more children from ages 12 to 17, more employed or self-employed work, more urban work and more work in services and industry, even though family work and the agricultural sector still provided the majority of jobs for children in the regions. Child workers were most likely to be out of school in Asia at rates between 32 and 35 percent and least likely to miss out on an education in Latin America at just 16 percent of child workers being out of school. Boys became child laborers only at a slightly higher rate when taking into account age-inappropriate domestic work carried out by girls. Globally, around half of child workers carried out hazardous work, defined as work likely to harm a child's health, safety or morals.