Compared with other countries, the growth of non-bank financial actors in China has been huge within the last decade. Despite the recent crack-down on asset flows moving away from traditional institutions, the Chinese government is still wary of the less regulated, digital banking and lending sphere as the recent halt of the Ant Financial IPO has shown.

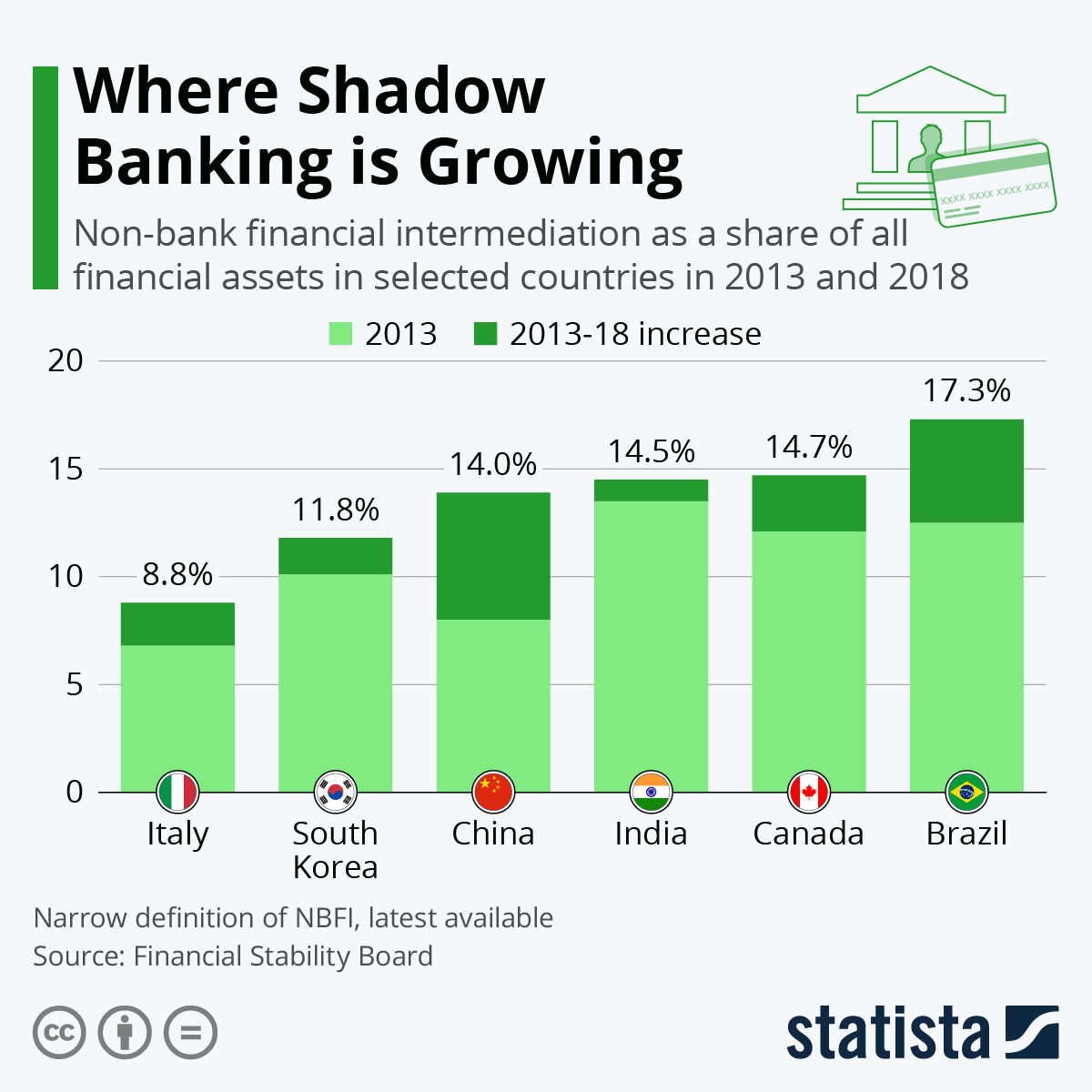

Data by the Financial Stability Board reveals that between 2013 and 2018, the share of non-bank financial intermediation as a share of all financial assets in China has grown from 8 percent to 14 percent, even though 2019 data released early next year will show how much government intervention has decimated the sector. The international body established by G20 nations after the 2008 financial crisis defines these NBFIs as “non-bank financial institutions involved in credit intermediation activities that may pose bank-like financial stability risks”. A report by PWC concludes that new regulations aimed at reducing this financial stability risk have reduced the sector somewhat, but that Chinese non-bank actors are nevertheless here to stay and deserve some recognition for extending financing opportunities where none existed before in the country.

Emerging nations have been associated with the growth of non-bank financial actors – often thought of as lenders in the digital sphere in recent years - but this is not always the case. Brazil, like China, has seen non-bank intermediaries balloon. In India, they have only shown modest growth while remaining at a high level. This is in connection with the long history of shadow banking in the country that has been relying on alternative means of credit in the face of highly regulated banks that could not serve large parts of the population.

Italy, South Korea and Canada are examples of developed nations where NBFIs have been growing as a share of total financial assets. All three nations experienced more modest levels of growth, however.