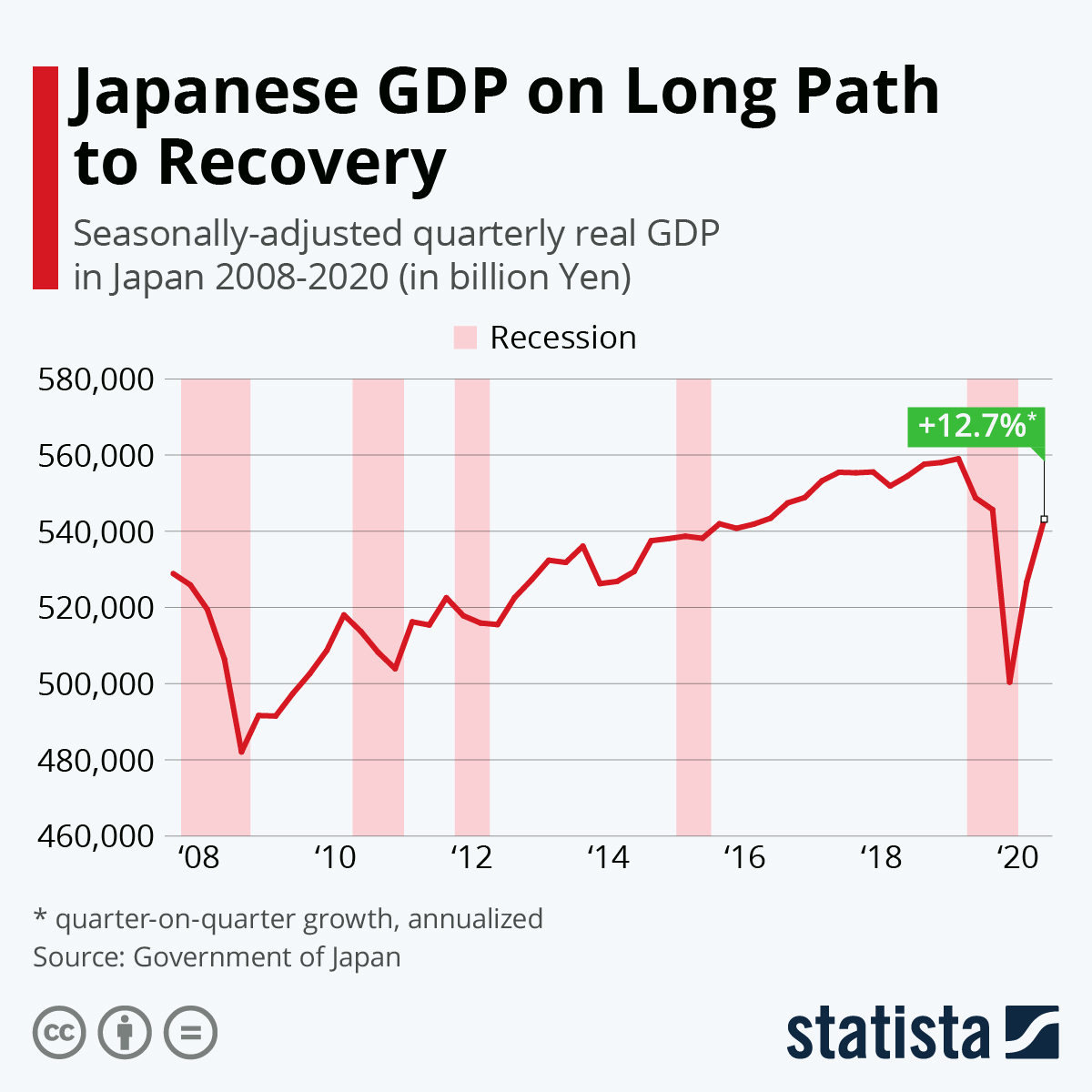

Japanese GDP contracted by 28.8 percent in Q2 of 2020 at an annualized rate, the biggest decline on record, before bouncing back 21.4 percent quarter-on-quarter in Q3 and 12.7 percent in Q4.

Despite the high growth rate, our graphic shows that Japanese national accounts are still lagging behind mid-2019 levels. While Q3 and Q4 could almost make up for the giant slump in Q2, the country also experienced two additional quarters of negative growth in Q1 of 2020 and Q4 of 2019, adding to the decline in GDP the country still has to catch up on.

In fact, the Japanese economy has been no stranger to recessions even before the coronavirus outbreak.

The country experienced three albeit milder recessions between the COVID-19 pandemic and the global financial crisis (when looking at quarter-on-quarter growth). The first was caused by the devastating earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011, while the other two and single negative growth quarters can be chalked up to the long period of stagnation the Japanese economy has found itself in since its asset price bubble burst in the 1990s.

In the aftermath of the crisis, Japan amassed a mountain of debt that it carries to this day. An aging population and a shrinking consumer market are other factors making it hard to revive the Japanese economy, as is the country’s continued reliance on exports and tendency to invest overseas rather than at home.

Former prime Minister Shinzo Abe promised the country relief through his “Abenomics” economic revival program but hasn’t lifted the country out of stagnation yet. The Abe administration significantly eased monetary policy and increased government spending, while simultaneously aiming for structural reforms to make the Japanese economy more competitive. Some of the reforms, for example getting more women to join the workforce, have been successful. Others, like increasing the inflow of foreign workers, still lack acceptance.